Searching for answers: Saint Rose students assist law enforcement in cold cases

November 8, 2021 · 2021

When forensic psychology student Caleb Linder ‘23 was 6 years old, Jaliek Rainwalker went missing. Rainwalker, who was 12 at the time and lived with his adoptive parents in Greenwich, New York, was last seen on November 2, 2007.

Linder’s grandparents lived in Salem, a neighboring town of Greenwich. The news of Rainwalker’s disappearance quickly spread. Local, state, and federal law enforcement led an in-depth investigation.

“I remember seeing his missing posters up,” Linder said.

Despite being one of the Capital Region’s most well-known cases, it remains unsolved today.

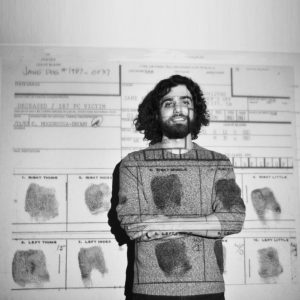

Nearly 15 years after learning about Rainwalker’s disappearance, Linder was assigned the Rainwalker cold case at the Cold Case Analysis Center (CCAC) at Saint Rose. A sophomore at the time, Linder was asked to join the CCAC by Dr. Christina Lane, program director and associate professor of criminal justice.

The CCAC obtained thousands of pages of information collected throughout the years by Jaliek’s maternal adoptive grandmother, Barbara Reeley. Linder’s job — alongside other students — was to read through the evidence, consolidate the most pertinent information, and try to find something that was overlooked in the past. This information was then passed to local law enforcement to help aid in their investigation.

Soon after being assigned the case, Linder made the connection. He called his grandparents and discovered they once lived in the same neighborhood as Rainwalker’s adoptive parents in Salem, a few years before Rainwalker went missing. Now there he was, playing his part in unraveling the case.

Rainwalker was last seen with his adoptive father Stephen Kerr, who alleges he ran away after they stayed the night at an abandoned family residence in Greenwich. In 2012, the case was elevated from “missing child” to “probable child homicide.” No arrests have been made to date, but Kerr remains a “person of interest.”

According to local news reports, Kerr told police they went to the empty residence after Rainwalker threatened another child at their home. The police have acknowledged that there are inconsistencies in Kerr’s story and there is evidence to back that up. Kerr and his wife, Jocelyn McDonald, maintained that Rainwalker is a runaway.

Rainwalker’s adoptive grandmother (Reeley) and his biological family are still searching for answers — answers that the Cold Case Analysis Center intends to help law enforcement agencies find.

“We are giving people peace of mind that not all hope is lost,” Linder said.

Warming up cold cases

The Jaliek Rainwalker case represents one of the hundreds of thousands of cold cases across the nation. According to the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, there were 250,000 unsolved murders nationwide in 2020 — a number that grows by 6,000 each year.

Dr. Chris Kunkle, a longtime adjunct in Saint Rose’s criminal justice department and deputy director of the South Carolina Department of Corrections, is familiar with the cold case crisis facing the United States. After years of witnessing a lack of resources dedicated to cold cases, Kunkle initiated the idea of developing a Cold Case Analysis Center at Saint Rose. A co-founder and advisor of the center, Kunkle felt confident in the College’s ability to help fill a gap while ushering in a new generation of law enforcement professionals.

“I saw that the possibility of the person-power of Saint Rose and what students could provide in helping organize files and researching things that law enforcement agencies, unless they’re well-funded, just don’t have resources for,” Kunkle said. “And, in kind, we could provide training and an education to students who would be potentially working live cases.”

The only center of its kind in New York State and one of six nationally, the Cold Case Analysis Center officially got its start in 2018. Each year, students from degree programs in criminal justice, behavior, and law, forensic science, and forensic psychology are selected to work on real cold cases — such as the Rainwalker case — under the guidance of Kunkle and Lane, and in partnership with local law enforcement agencies.

Students like Linder and Molly Tasber ‘22, a criminal justice, behavior, and law student with a concentration in criminology, gain real-world experience they can apply to their future careers.

“This has really helped me want to be an investigator because I see things in reports, and I’m like, ‘Ah, I want to be able to fix that for the future,’” Tasber said. “And I want to be able to help people so that they don’t become a cold case.”

Tasber is graduating this spring and is thinking about joining the police academy. She has worked on three cold cases to date: the Jaliek Rainwalker case; the Suzanne Lyall case, which focuses on a student who went missing from the University at Albany campus in 1998; and most recently, she was assigned a case that focuses on finding the parents of a baby whose body was found in 1997.

When working in the Cold Case Analysis Center, Tasber said students hear from guest lecturers who are experts in the field, such as police officers, FBI agents, forensic pathologists, and forensic anthropologists, who all lend their insights to the cases at hand.

They also learn about modern-day technologies integral to solving cases, such as genetic genealogy and advanced DNA testing.

“I didn’t realize how much truly goes into the cases and how many people really work on them before they turn into a cold case,” Tasber said.

Lane said students are quick to realize that working on cold cases is nothing like what is portrayed on TV shows.

“There’s a lot of rigor involved, and research, and deductive and critical thinking,” Lane said.

Lane knows all too well what it’s like to live in a community impacted by an unsolved crime. She lives in Cambridge, a neighboring town of Greenwich, where Jaliek Rainwalker went missing.

“And being part of that community and knowing that the community really cares to know what happened to him, really made me gravitate to that case to see if we can give any assistance or help,” Lane said.

The goal of the CCAC is to help keep these cases alive by resurrecting new evidence and providing better information to law enforcement.

And the CCAC has been successful in doing so.

While investigating the case of Catherine Blackburn, who was sexually assaulted and brutally murdered in Albany in 1964, the Cold Case Analysis Center, in conjunction with the American Investigative Society of Cold Cases, donated money to have DNA analyzed through a process called M-Vac.

By forging ahead with this process, local law enforcement and forensic laboratories were able to isolate potential suspect DNA and rule out suspects as a result.

“That catapulted that case closer to resolution,” Kunkle said.

Helping the dear neighbor

True crime content has exploded in popularity since the podcast “Serial” first captivated millions of listeners in 2014. But, it does take a certain type of person to want to actually do the work and study the worst details of unimaginable crimes. As Lane puts it, they’re looking at “the dark side of life.”

So, why do it?

Helping the community is central to the mission of Saint Rose, which is why developing a Cold Case Analysis Center here was a natural fit.

“The Cold Case Analysis Center is providing a resource to the community as a way of giving back,” Lane said.

A large part of the CCAC is developing trust with local law enforcement. Over the years, the Albany Police Department has recognized that Lane, Kunkle, and their students are a great resource for the community. So much so that the Albany Police Department selected cases for the program to focus on this fall.

“They pick and choose the cases that they think would be the most viable, meaning the ones that actually have a lot of physical evidence to them,” Lane said.

There is a reason why these cases are cold. Progress is seen in fits and starts. But the Cold Case Analysis Center has time. As each year passes and new students come in, the program inches closer to helping law enforcement find the missing link. What’s most important to Lane and her students is that these victims are not forgotten.

“Our students, who are learning and applying all the academic knowledge in a practical sense, are actually giving back to the community and helping victims of crime,” Lane said. “We are letting them know that these cases still mean a lot to police officers. They are not forgotten.”

— By Caroline Murray