Wayde Dazelle ’16: Addressing public health inequities through medicine, creativity – and lots of energy

October 18, 2020 · 2020

You’d think that earning an M.D. wouldn’t allow time for anything else. But, even as a fulltime medical student in his second year at George Washington (GW) University’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences, somehow Wayde Dazelle also finds time to volunteer at clinics and work as a health economist on multiple large research projects.

One, at the maternal fetal department at GW and funded by a National Institutes of Health grant, is studying the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of tranxemic acid to prevent maternal blood loss after childbirth.

Another, with Children’s National Hospital, is a nutrition intervention for communities struggling with food insecurity. Families receive weekly packets of vegetables, fruits, nuts, and other healthy foods, with guidance for their use.

“A lot of participants might not be too familiar with butternut squash or parsnips,” says Dazelle. “We include resources to help them understand how to cook and potentially incorporate these things into the foods they already enjoy to make them a little healthier.”

In addition, he works as a biostatistician with OB/GYN residents and GW faculty to analyze the relationship among body mass index, quantitative blood loss, and complications in women undergoing cesarean section.

In only four years since he completed his undergrad degree at Saint Rose, Dazelle has racked up a head-spinning array of experiences: He’s developed and managed education programs for healthcare workers in Haiti. He’s collected and analyzed research data on tuberculosis in Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, and Zambia. He’s directed an initiative to support and advocate for disadvantaged young women in Uganda. And he’s earned a master’s in global health policy and management at Brandeis.

From academic indifference …

It’s a shock to hear that he wasn’t a good student in high school.

“As a kid, I had trouble wanting to learn certain things,” explains Dazelle, who suspects that he had an undiagnosed attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. “We’d be reading ‘See Spot Run,’ and I’d get in trouble because I wouldn’t read the book they wanted me to.”

But he had one interest that could open academic doors: music.

“I could delve deeply into really technical applications of music theory and extended performance techniques, and that was something I could leverage to get a college education,” says Dazelle.

He started at Saint Rose as a music education major and jazz performance minor (sax is his axe). He loved it, but a momentous event during his first year dramatically changed his focus.

His mother, who had battled breast cancer, was rediagnosed with multiple metastases. Dazelle became her main caregiver, commuting back and forth to the family home near Springfield, Massachusetts, to help with medications, meal prep, and doctor’s visits.

It wasn’t his first caregiving gig: As a child, he had taken care of his chronically ill father, who passed away when Dazelle was 11.

“When I was in half-day kindergarten, the other half day I’d be helping him with his medication at home.”

And he observed his mother’s healthcare providers. Closely.

“I started to identify areas where medicine was doing very well, and areas where it was really deficient,” says Dazelle. “That spurred a lot of interest and motivation.”

When his mother passed away the summer after his first year, Dazelle was determined to make medicine a bigger part of his life. He wasn’t sure which direction to take – clinical or regulatory – so he changed his major to philosophy, medical ethics, and minored in public health.

“I could have a foot each in the regulatory domain and in the clinical domain, and leverage Saint Rose’s resources in both areas,” he says.

… to finding a calling

He hit his stride immediately, finding mentors in faculty members Richard Pulice, Stephanie Bennett-Knapp, and Mustapha Marda.

“They really pushed students to reevaluate existing systems and not presuppose that our systems are necessarily the best,” says Dazelle.

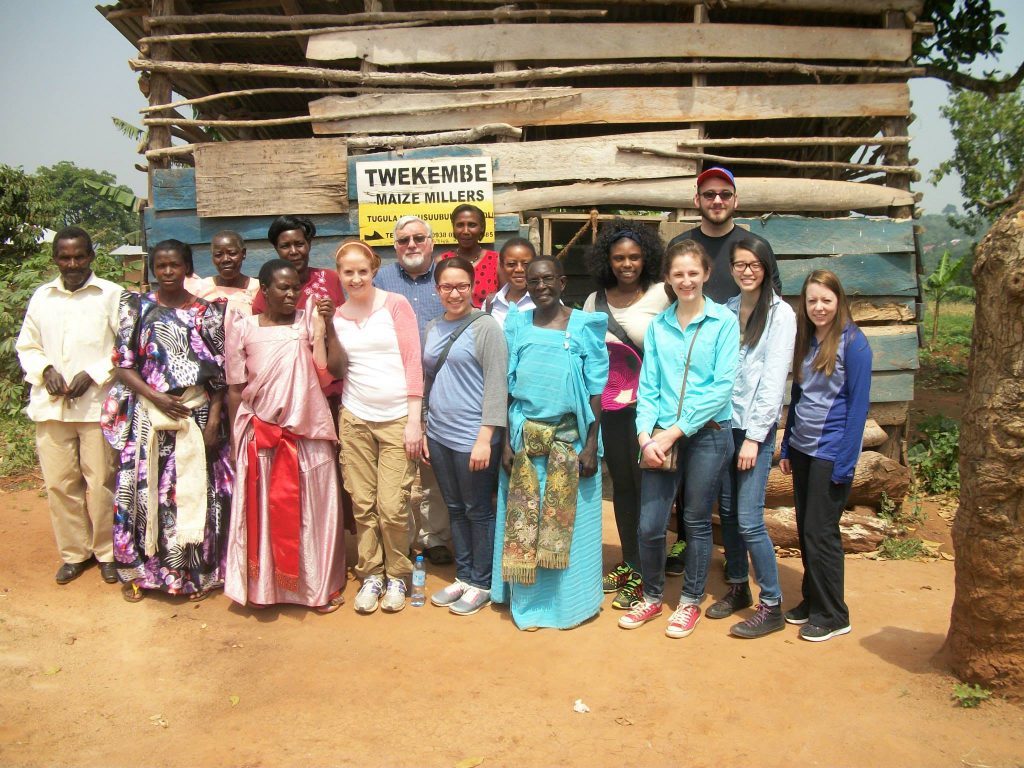

Pulice tapped Dazelle to participate in a grant project in Uganda.

“That was one of the most interesting and impactful experiences for me – the development of economic support programs for women who were victims of domestic violence and seeing how they overcame that violence to form a self-sustaining community,” says Dazelle.

He worked on several other independent projects with Pulice.

“We were able to do far more advanced public-health learning, far more advanced epidemiology training that went far above what most students have access to.”

He collaborated with Bennett-Knapp on high-level epidemiological analysis work. With Marda, he studied the U.S.’s involvement in developing countries.

With his interests in women’s reproductive health and his experience with his mother, Dazelle found himself inexorably drawn into women’s health. He was sure he wanted to go to graduate school, but unsure in what capacity, so he applied to 20 law programs and 20 medicine-focused programs.

He was accepted into all but one.

Realizing that he found medicine much more exciting than law, Dazelle chose a post-baccalaureate pre-medicine program at Brandeis, followed by the master’s in global health policy.

Toward equity in medicine

Ultimately, Dazelle plans to become a practicing OB/GYN physician in an academic setting, so he can practice medicine while continuing with economic and policy research.

“In the U.S., our patients pay more for worse outcomes. As a health economist, I have a passion to identify some of the inefficiencies in our system.”

That could include addressing the needs of specific populations, such as LGBTQ individuals, and tackling racial and socioeconomic inequalities.

“Nationally, Black women are three times more likely to die in childbirth than white women,” says Dazelle (in D.C., that ratio is more like five times, he says).

Whether disparities are caused by huge healthcare conglomerates crowding out local hospitals that tend to lower-income, inner-city patients, or by individual providers discounting the complaints of minority patients, Dazelle is eager to tackle systemic problems exacerbating inequity in healthcare.

He credits Saint Rose with giving him a strong career foundation, and loves the accessibility of faculty to students for independent learning.

“The ease with which students can meet them, their willingness to make the time and effort to facilitate those working relationships with energy and excitement, that’s something unique to Saint Rose.”

He felt that way as a music student, too.

“When I was a high-school student auditioning at different schools and conservatories, I noticed there was something about the community in the music school at Saint Rose – a lot of internal support and opportunity for individual development,” he says. “You name it, you have that opportunity. Saint Rose invests in the individual. They really care about the person.”

By Irene Kim