Vickery Speaker: Looking at Racism in Health Care and Health Outcomes

November 8, 2017 · News

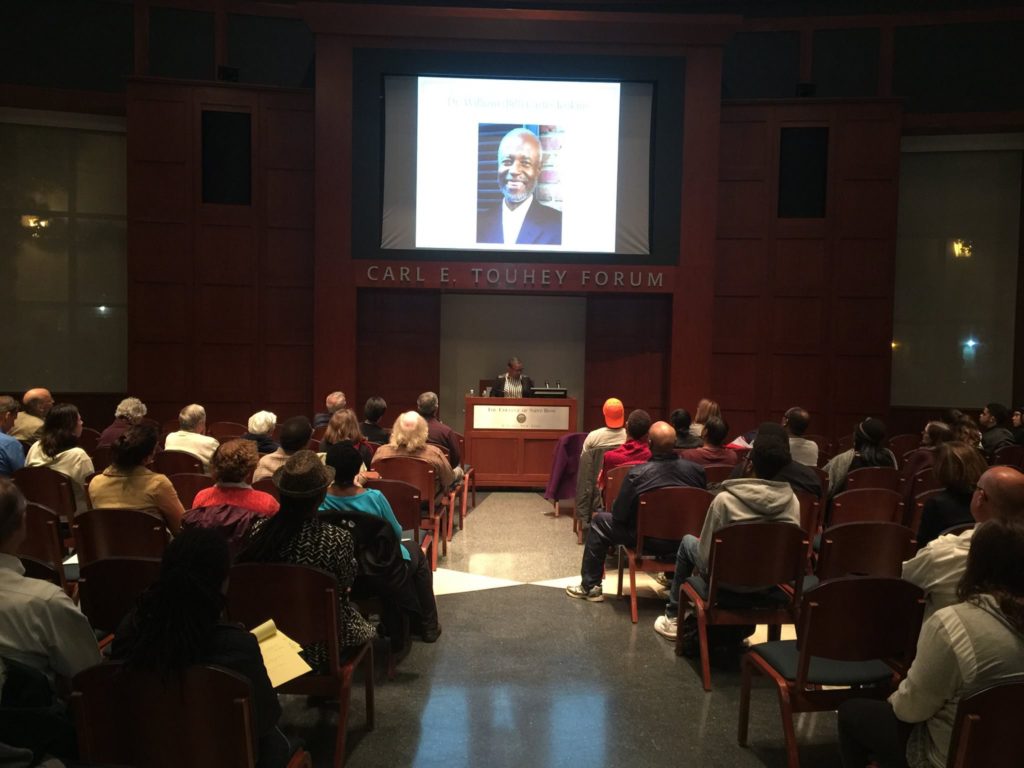

Dr. Vanessa Northington Gable speaks about race-based medical inequities during the Vickery Lecture Series at Saint Rose in November 2017.

As a sophomore at Hampshire College in 1972, Vanessa Northington Gamble read the Associated Press article that was to define her career. She and millions of other shocked Americans learned that the U.S. Public Health Service had, for 40 years, studied hundreds of African-American men infected with syphilis. Government workers had left the patients untreated without informing them that they were infected.

In the immediate term, Gamble based her senior thesis on the study; in the longer term, she shaped her career around it.

“My life changed to look at the history of racism in U.S. medicine,” said Dr. Gamble, an MD/Ph.D. medical historian who in November gave Saint Rose’s prestigious Vickery lecture. Gamble, a professor at George Washington University who has served on the faculty of many prestigious universities, chaired the committee that secured a 1997 Presidential apology to the survivors of the U.S. Public Health Service’s Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.

The Public Health Service began the study in 1932 in rural Macon County, Alabama, looking at about 400 men who had syphilis and about 200 who did not; many were relatively poor and uneducated. The study, designed to observe the progression of the disease in African-American males, was originally scheduled to run for six months but was indefinitely extended to follow the disease to its “endpoint,” or patient death. The men were dissuaded from seeking outside treatment, even when penicillin became the treatment of choice in 1945.

The study continued until 1972, when a whistleblower leaked the details to the press.

Institutional crimes

Professor Tina Lane, Saint Rose’s sociology and criminal justice chair, teaches the syphilis study to illustrate how a government institution can endanger and injure people.

“There is an assumption that, if something is done by the government, it must somehow be for the eventual good,” she said.

The study’s organizers, explained Gamble, strategically captivated the patients with culturally sensitive incentives, such as otherwise-unaffordable medical treatment and burial insurance. The study’s organizers enlisted the help of community churches and schools and partnered with the local Tuskegee Institute, an organization founded and largely run by African-American principals.

“They enticed the patients with benefits they would not otherwise have received,” said Professor Stephanie Bennett-Knapp, coordinator of public health in Saint Rose’s department of social work. “They used the people’s humanity against them.”

Public revelation concerning the study, and its subversion of the physician oath to do no harm, unleashed shock and outrage. “Stories like this destroy our trust in society and decay the fabric of society,” said Lane. The study was often cited as a major reason for black Americans’ refusal to participate in HIV studies in the 1980s and 1990s, and even sparked rumors that the government had created the virus to wipe out African-American communities.

“Events like the syphilis study make it hard for people to trust doctors’ interventions,” said Bennett, adding that some U.S. Muslim communities have refused to vaccinate their children against measles out of fear of unfounded links between the vaccine and autism. “As a result, many of their kids have gotten measles, and there have been many deaths.”

The entrenchment of medical racism

While the syphilis study looms large as an example of medical racism and symbol of many African Americans’ distrust of the health care system, both racism and distrust predate the study, said Gamble, and extend back to slave-ownership times. History is rife with examples of experimentation on nonconsenting black subjects, e.g., J. Marion Sims’s gynecological experiments on slave women in the 1800s, rampant robbing of African-American graves – often to supply Northern medical schools with cadavers – in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the theft of Henrietta Lacks’s cells.

Many of these abuses grow out of a tradition of viewing African Americans as biologically inferior, said Gamble, and for that very reason more susceptible to diseases such as tuberculosis. Nineteenth-century sociologist W.E.B. DuBois countered these attitudes by pointing out that many health problems were due to substandard housing, nutrition, and environment.

To this day, racism remains manifest in health care for black and other minority patients – from receiving substandard neurological care, to being denied painkillers because of suspicions that patients might be drug addicts. A 2016 research study found that a disturbing number of medical students and residents believed inaccurate, often outlandish, physiological myths about African Americans – from having blood that coagulates at different rates than whites’ blood, to having thicker skin and smaller brains.

“These are all little ways in which we rationalize the belief that certain groups are not really part of the moral community,” said Michael Brannigan, Saint Rose’s dean of spiritual life and the Pfaff Endowed Chair in Ethics and Moral Values. “They don’t have the moral status that the rest of us have.”

Annette Ramirez ’17, who like Gamble focused her senior thesis on medical racism and aspires to a medical career, said that she notices unconscious bias perpetrated in the medical curriculum. “You try to teach people not to be biased, but even in the literature, they categorize certain races with certain diseases – so it’s hard not to associate the two,” said Ramirez, who is earning an M.S. in biology at Lehman College.

“As a person, you have to not look at race, and just look at the facts,” she added. “This patient is coming in with these symptoms; this person doesn’t have these symptoms because of their race.”

Learning from one another

Gamble is quick to remind that there’s another side of black medical history: the hospitals that emerged in response to white hospitals’ refusal to admit black patients and health care professionals. She points to numerous African-American health care pioneers whose accomplishments defied discrimination, such as Virginia Alexander, who used her influence with the Quaker community to combat medical racism; Vivien Thomas, who, despite being denied entry to medical school, invented the surgery to save children from “blue baby” syndrome and taught generations of surgeons; Edith Irby Jones, the first black medical student to attend the University of Arkansas medical school; Dorothy Ferebee, who energized a sorority of black female students to provide health care to impoverished Misssissippi citizens; and Halle Johnson, the first female African-American doctor in Alabama.

To fight racism in our own lives, Gamble suggests replacing the term “cultural competency,” which implies that one can overcome racism by attaining a benchmark, with “cultural humility.” “That way, you emphasize lifelong learning,” said Gamble. “The patient becomes the teacher.”