Dorothy Fitzgerald Nealon ’46: Study-Abroad Pioneer

October 24, 2017 · Alumni

In 1945, traveling abroad to study for college was rare, especially for women. Dorothy Fitzgerald Nealon decided that it was time that she and her classmates learned Spanish in a country that spoke the language fluently. And thus the international study programs for Saint Rose were born.

On May 8, 1945, Saint Rose junior Dorothy Fitzgerald (later Nealon) ’46 found herself among thousands of happy people celebrating the end of World War II. She wasn’t in downtown Albany; nor was she in Times Square kissing a sailor. She was in the Zócalo, the central plaza of Mexico City, where she and four classmates were studying abroad.

It was the College’s first-ever international study trip – and entirely Nealon’s brainchild. She’d had the idea the year before, when she read about an Ivy League student traveling to the Sorbonne to improve her French. “I thought, ‘If I’m studying Spanish in Albany, I’d be much better off learning it somewhere else,’” said Nealon, who was majoring in Spanish and English.

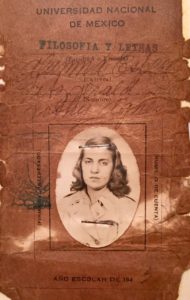

Dorothy spent a full year studying Spanish culture and literature at the National University of Mexico.

To Sister Thomas Francis, the director of the College’s Languages department at the time, she floated her proposition: Take a group of students to Mexico to learn Spanish in a completely immersive, sink-or-swim environment.

The director loved the concept and immediately sought the ear of the President, who approved the plan. With the help of a Benedictine priest with teaching connections in Mexico, Saint Rose developed a program whereby students would receive credit for a year of studying at the National University of Mexico.

Little did she dream that study abroad would become a key component of the College’s global connections – which now encompass semester and summer options for students in almost 30 countries. “We also send students with Saint Rose professors on short-term faculty led programs to Italy, France, The Netherlands, Ireland, Poland, Panama, and many other locations, representing disciplines such as Art, Music, Social Work, Communication Sciences & Disorders, Psychology, and Spanish,” said Colleen Thapalia, interim director of the Center for International Programs.

It all grew from Nealon’s inspiration, nearly three-quarters of a century ago. “I gave them the idea and they worked out the details,” said Nealon. “I just had to talk other girls who were taking Spanish into going along.”

Few U.S. students, especially women, went abroad in those days, but Nealon had little trouble finding interested classmates. “I think kids get kind of bored around sophomore year,” she said. “They probably all thought that it would be good to get away and get credit for it.”

So, in February 1945, she and Cathryn Buckley (Arcomano) ’46, Anna May Falaytn (Provenzano) ’46, Catherine Doyle (Duncan) ’46, and Marion Arcomano (Texier) ’46 boarded a train to Texas, then a plane to Mexico City.

Initial accommodations were grand: “The College had arranged for us to live in a great big house that was built around a patio; all five of us were in one big bedroom with five beds, like a dorm,” said Nealon.

At the back of the house, the women noticed a number of rabbits in cages. But it was some weeks before they could identify the mystery meat served at each Sunday dinner.

“That’s when we decided to move,” laughed Nealon.

The group quickly found and rented a modern, sixth-floor apartment in downtown Mexico City. They had a huge chunk of the day free to dine, shop, watch movies, and even nab parts as extras in a film: Since their professors were teaching as a secondary job after working their day jobs, most classes didn’t start until 4 p.m.

In the classroom, the group studied Spanish literature and culture. Outside the classroom, they received a crash course in the language. Although friendly and helpful, none of the neighbors spoke English, and the women quickly became fluent Spanish speakers. “We were living it all day,” said Nealon. “We were taking cabs and going to lunch every day, talking to people constantly.”

After their year abroad, the students came back to Albany for senior year. Nealon went on to teach Spanish at the College for a short stint after graduating, then taught English at Schenectady High School until retiring. She returned to Mexico many times, vacationing in Acapulco with her family and relishing the opportunity to practice her Spanish.

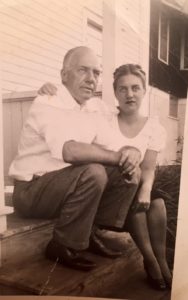

Dorothy comes from a family that has proudly supported education for women, and her beloved dad was a huge proponent.

Nealon, who comes from a family that highly values education, pointed out that her insurance-salesman father was fond of saying, “The best life insurance for a woman is a college degree.” And, said daughter Patricia Schiraldi, Nealon’s example – earning undergraduate and graduate degrees as well as launching the College’s first international study program – continues to inspire younger women.

Case in point: Granddaughter Laura, who majored in international relations at Northeastern, worked with the United Nations in Switzerland and the European Union in Belgium during her own study-abroad trips. Without Nealon’s trail-blazing precedent, would those opportunities even have been available?

Nealon is, sadly, the only remaining member of that first international-study group. But she’s looking forward to the publication of classmate Buckley’s letters, compiled by Buckley’s husband, Nicholas Arcomano (brother of classmate Marian Arcomano).

“It just takes one person to open the door, and Dorothy did that,” added Thapalia. “The door she and her friends opened when they traveled to Mexico has led to hundreds of students going to dozens of countries.”

Seventy-two years later, the benefits of that first trip live on. Apart from the language, Nealon learned many lessons. “The trip made me much more tolerant of things I wasn’t used to, and it gave me a desire to travel, get around the world, and see things.”